The Life of an International School Kid

As you all know by now, the kids are going to an international school in Denmark. When moving over here, we knew we had the option to put them in public school, which is taught in Danish, or to pay and enroll them in a private international school, where they would learn in English.

Obviously, the kids were concerned about going to a public school if they couldn't speak the language, and Zac and I were concerned about committing to private school tuition for three kids when we already weren't exactly sure how our budgets and taxes and everything were going to shake out. In sum: we were a little unsure what to do.

Eventually, we decided to enroll them in the international school. We knew the move would be hard on them already, and we didn't want to add a level of difficulty with their education. Besides, we weren't sure if we were going to stay in Denmark more than two years, and it wouldn't make sense to put them through that trial if we were just going to end up back in the U.S. We also figured that they would get Danish language classes in their English-speaking school, and eventually, if we did stay in Denmark, we thought maybe they could choose to transition to a Danish public school when their language skills improved

* * *.

Now that the kids are a little more established, we thought it would be a good time to ask if they wanted to change to Danish school next year and save us some money! They haven't learned much Danish, so we knew this would still be a challenge, but maybe they would be more prepared to handle it now.

None of them were quite sure how they felt about it, so I reached out to the Americans in Denmark Facebook page to see if anyone else with kids of a similar age had started their American, English-speaking kids in Danish public school, or if anyone had started their kids in international school and then moved them later to Danish public school. I needed insights!

The responses overwhelmingly convinced me that we made the right choice. We are keeping the kids right where they are.

* * *

To summarize the experiences relayed by the other American parents:

- Integrating international kids into a class of Danes is difficult socially. The Danish students in a class have been together a long time (because in Denmark, you move up through the grades with your same classmates in the same classes), and the farther along the kids are in school, the more your kids will struggle to break into the long-standing friend groups.

- Along these same lines, many parents (including Danish a school teacher in the public system) witnessed the Danish school kids actively shunning anyone who was different, whether they were someone from another country or just a Dane who had moved and started in a new school. The new kids were lonely and struggled to make friends, and sometimes, they were bullied.

- The public schools would like to provide individualized support for non-Danish-speaking immigrants, but the reality is that most of the public schools do not have the resources to do so.

- Grades 7-9 are geared toward passing the 9th grade exams (after which students head down different educational paths based on what they want in the future), so the stress and rigor of the education system really picks up in those years. It would make integration at this point extremely difficult for Kaden and Khloe. They would need to not only quickly get familiar with the different Danish school tracks, they would need to be able to sit for exams (in Danish) and do well enough to continue on the track of their choice. This is difficult even for some Danish kids.

- Parents felt that teachers in the public system expected the children to be as fluent in Danish as their peers, and tended to treat the children who are trying to integrate into the new culture the same as they treat the Danish kids. For example, they assumed the non-Danish children were familiar with Danish cultural behaviors, songs, games, and routines, so instead of explaining them and ensuring the newcomers felt secure in what was happening, they were kind of left behind. I'm sure the teachers are not aware that they are being exclusionary because it's hard to recognize when you're making assumptions and being biased by your own experiences, but it is hard to change, too.

- As mentioned, the kids aren't learning Danish very quickly. They are taught in English, their teachers and friends speak English, and they are never forced to speak Danish except in their Danish classes at school.

- Many international school kids are transient. Maybe their parents are here on temporary contracts, or maybe their parents work in a job that requires them to move around the world every couple of years. Either way, our kids have helped welcome several new students to their classes in the last year and a half, and they have also had to say goodbye to friends and classmates as they move away. It's a little hard to watch a friend go when you only have a few close ones.

- There are not so many international schools, so the kids in a class tend to come from places within maybe a 30 km radius rather than a single neighborhood. This makes it trickier to see friends outside of school, and you don't often run into your friends outside of school hours or get to travel to and from school with them.

- Once you finish your primary and secondary educational years in an international school, you really only have the option of going to an international high school (gymnasium) (as opposed to a regular Danish gymnasium) if you want to stay in Denmark. There are public international gymnasium schools, but there is only one in our area, and to get in is quite competitive. There are also private international gymnasium programs, but that means we would keep paying tuition... Further, without speaking Danish, you cannot go to a Danish trade school to learn carpentry or painting or welding or anything, you can't go to a standard Danish gymnasium, and you can't go to Danish university.

I was born and raised in north Idaho, which means I wasn't really exposed to any school system other than the one I was a part of. In the U.S., it generally goes like this:

School starts in late August or early September and ends in early June. The summer break is almost three months, or 12 weeks (unless kids attend private, year-round schools). There is a break from about mid-December to just after the New Year for Christmas, and there is a week off for Spring Break in the Spring. There is also usually a week off at Thanksgiving in November.

Ages 0 to 3 years: Mostly passive education. You might be cared for by a parent or babysitter or a private (for-profit) daycare center, and you probably have someone reading to you, teaching you about shapes and colors, and helping you work on your social skills and fine motor skills.

Age 4: Many kids are enrolled in a (for-profit) pre-school/daycare where someone starts teaching you all the stuff you need to know before you go to kindergarten. You work on your letters and numbers and singing and all that other stuff I mentioned before.

Age 5: Many kids go to kindergarten. There are private kindergartens that cost money and public kindergartens that do not. Some are half-day and some are full-day. You start learning to read and tie your shoes and put on your own coat when you go outside. Kindergarten is not required.

Approximately ages 6-10: This is elementary school. It's required. It's 1st grade through 5th grade. In some cities, 6th grade is also included in elementary school.

Ages 11 or 12-13 or 14: This is middle school and includes 6th through 8th grade. If 6th grade was included in your elementary school, then this is only 7th and 8th grade and is called junior high instead of middle school. You can take a trip to Washington D.C. to learn about government in 8th grade (if you come up with the money).

Ages 14 or 15-17 or 18: This is high school and includes 9th grade through 12th grade. You call 9th graders "freshmen," 10th graders "sophomores," 11th graders "juniors," and 12th graders "seniors." In high school, you start learning a language. (In states that are not Idaho, and also in private schools, many kids start learning a language as early as preschool or kindergarten, but I'm just telling you how the Idaho public system works, which is similar in operation to many other public school systems in the U.S.)

From kindergarten through high school, you can attend public school for free or private school, which charges tuition.

After you graduate with a high school diploma, you can choose to enter the workforce, go to a trade school (e.g. to be a diesel mechanic or a hairdresser), go to a community college for two years to take some general subjects and figure out what you want to do in life, or go to a 4-year university to pursue a Bachelor's degree.

If you didn't pass high school or if you dropped out, you can get a high-school-equivalent degree called a GED.

If you go to community college, you can transfer to a 4-year university later, or you can receive an Associate's degree in a variety of subjects that allow you to go out and get a job.

And then, of course, after a 4-year degree, you can go on to get a Master's or a Doctorate, and you can even do post-doctorate studies beyond that.

Why do I know all of this? Because I was raised in this system! No one sat down and spelled it out for me. It was part of the common vernacular. I knew people at all stages of this educational system my whole life. It was basically passive knowledge.

When you're moving to a new country, you don't have a clue about anything. You find yourself in your 40s unable to answer a simple question about the education system where you live. When your kid asks, "What grade will I be in at my new school?" you just kind of spiral.

Do they call the school years "grades" here? Does school still start at the end of summer and end in June?

Do kids go to school the same number of years in Denmark as in the U.S.? What about the rest of Europe? Are there still standardized tests?

How are the schools divided up? Will all my kids be at the same school, or will they all be at different ones?

Are there school busses? How do kids get to school? Do they need to bring a lunch? Is there a school supply list?

You can ask people who live in the new country about the school system, but remember, they are coming from a position of having all this knowledge passively, so sometimes when they answer, they are accidentally assuming you have their same baseline knowledge, and the answer isn't super helpful. And until you figure out that international schools in Denmark operate according to the British system, not the Danish system, it will be very confusing.

* * *

The international system is close to the U.S. system in many ways. Here's how the international system works (as best as I have learned, because I have only been exposed to it for a year and a half and not my whole life):

School is essentially year-round. It starts in mid-August and ends at the very end of June, so July through mid-August, there is a 6-week summer break. There is Christmas Break from mid-December until after the New Year, there is Winter Break for a week in February, Easter Break for a week in April, Autumn Break for a week in October, and a few other random days off throughout the year. International schools are private and require tuition.

Ages 3-4: This is known as "Early Years" and is part of the primary years program. Kids start learning to read, write, and count. Similar to pre-school in the U.S.

Age 5/6: This is Year 1 and is basically the U.S. equivalent of kindergarten.

Age 6/7: Year 2, equivalent to 1st grade in the U.S. system. From here, you keep going up through the primary years program until Year 6, which is essentially equivalent to 5th grade in the U.S.

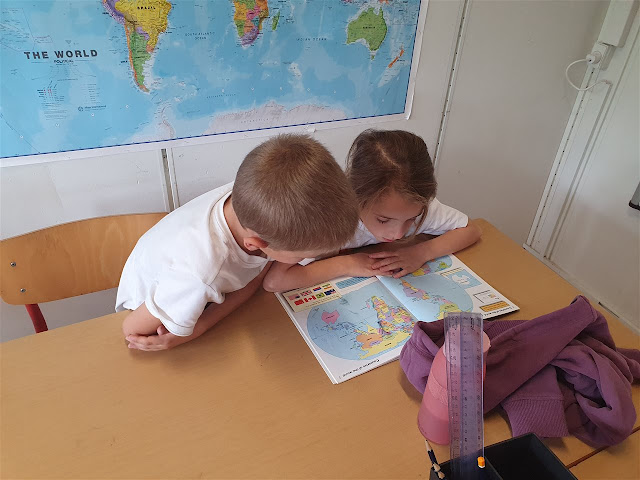

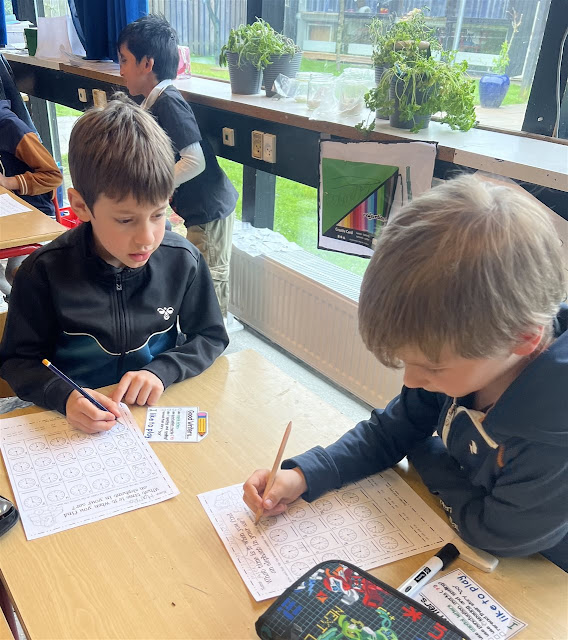

After the Primary Years Program, students enter Lower Secondary, which is Years 7, 8, and 9, equivalent to U.S. grades 6-8 (so like middle school in the U.S.). You start learning a language. You take a baseline exam when you start Lower Secondary, and you finish with a checkpoint exam. You go on class trips to explore other places and learn about other cultures.

After Lower Secondary, students start Middle Secondary, which is Years 10 and 11, equivalent to U.S. grades 9 and 10. They do not use the terms "freshman" or "sophomore" in this system. In Middle Secondary, you start specializing your areas of study, you job shadow in the real world, and you do community service hours. You go on class trips to other countries here, too.

After Middle Secondary, you go on to Upper Secondary, which is Years 12 and 13, equivalent to U.S. grades 11 and 12. Again, they don't call them "juniors" or "seniors" in this system.

So it's not entirely different than the U.S. system. There are some aspects of the international system that are a little strange to run into as an American though.

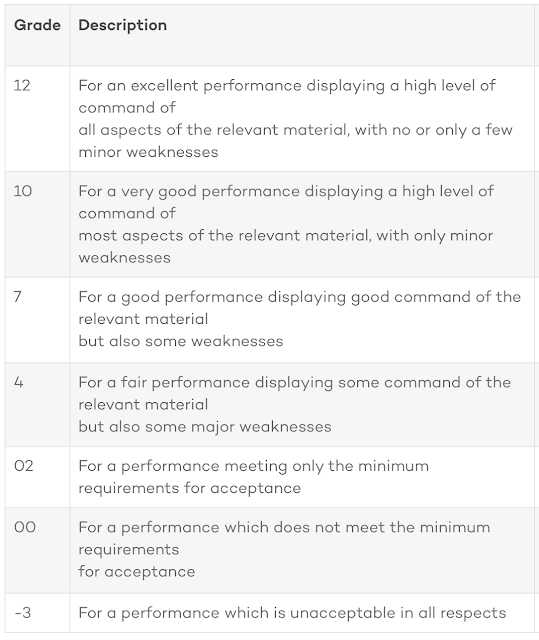

Grades

In the U.S., kids are graded on a system of A through F. In most cases, the breakdown is:

90-100% = A

80-89% = B

70-79% = C

60-69% = D

0-59% = F

Generally, a C is required to keep moving through normally, but a D is considered passing, and sometimes, a "plus (+)" or "minus (-)" is given out with the letter grade to differentiate where a student's grade lies within each tier.

In the international system, grades are assigned like this:

So there are similarities, but the breakdown is a little different, a 40% is still passing, and you can get an E, a G, or a U (although, I think U means "ungraded" or something).

Titles

In the U.S., kids refer to their teachers with a title and their last name, like Mr. Potts, Mr. Pullins, Mrs. Ritchie, Miss Bates, etc. In the international system, students call teachers and administrators by their first names.

Language

International school is taught in English (except for the language classes, of course), but it's British English, not American English! This is normally not too different or weird, but I've noticed that Harrison, who started 1st grade in the international system (Year 2) calls a period a "full stop." He also says some things in a more British way than an American way. One that I notice a lot is that instead of asking something like, "Is it supposed to go here?" he will say, "Is it meant to go here?" Or "Was I meant to build that part first?" instead of, "Was I supposed to build that part first?"

I noticed that Khloe's question intonation has changed to be more British English-y than American English-y, too. You'll just have to talk to her to hear that, though. :)

Discipline

The disciplinary practices in the U.S. were mostly punitive. If it was suspected that your inappropriate behavior was brought on by something serious happening in your life, you might go to the school counselor instead of into the disciplinary system, but typically it went like this:

- Verbal warning issued for first behavioral offense. A teacher tells you to stop doing whatever it was you did. This might be followed by a trip to the hallway if your behavior was disruptive. You might be given a little task to do as you sat outside the door waiting for the lesson to finish.

- For the second or subsequent offense, you often got sent to the office and/or "written up." This is where documentation of your behavior started to be on the record. You often just sit in the office for the remainder of class.

- After maybe 1-3 verbal warnings or write-ups, you would be issued detention. It might be in-school detention or after-school detention. Usually, a parent had to acknowledge this punishment with a signature.

- After multiple detentions, or if you broke a really serious rule, you could be suspended from school for three days. Again, a parent had to acknowledge with a signature, and there was usually a phone call.

- If you did something unforgivable or had repeated serious offenses, you could be expelled from school. That rarely happened, but it did happen.

The international school has a little bit different approach. They believe that it is in the best interest of a disruptive student to stay in the class and refocus their behavior. To isolate them from the learning environment or to punish them doesn't get to the core issue, so they want to ensure students are taking responsibility for their actions, understanding and reflecting on which behaviors were undesirable, and work with them to get them back on track as quickly as possible. In this system:

- The teacher gives a verbal warning to the student.

- If the behavior is continued, the student can be moved to a focus table in the classroom but away from their normal seat. This way, they can still participate in the lesson, but the act of getting up and resetting in a different space can often reset the expectations for behavior and help the student reintegrate faster.

- If the focus table is unsuccessful, the student might get sent to go have a conversation with the head of their department (like the head of secondary). The conversation will be focused on ensuring the student understands what they did and how that impacted the teacher and other students, as well as their own learning time. They will often be asked to sit and write down their reflections and then go over them with the class teacher and the head of the department. The parents will be called and sometimes be asked to come sit in on that meeting before the student can return to class, with a focus on finding root cause of the behavior and finding out what the student needs to help bring it back around.

- Repeated problems definitely result in a meeting with the parent, but again, the focus is on the needs of the student. What can help them be more successful? Do they need accommodations? What is the root cause of the behavior? Is the learning environment wrong for you? How can I help as a parent? Do you need a new style of planner or a special fidget to take to class? How can so-and-so help as the head of the department? How can the teacher help you?

The parent(s), student, department head, and teacher(s) come up with team plan: [student] will start wearing noise canceling headphones during classwork, [parent] will create a dedicated space at home for homework or buy their student a little notebook for organization, [teacher] will remind the student what they should be working on before the behavior modification steps are initiated next time, etc. Sometimes, the student is offered a day off of school for reflection if the student thinks it would be helpful to have a mental break. If the school suspects there is an undiagnosed neurodivergence, they will refer the student to be evaluated so they can get the tools they need to succeed as part of the class.

So all in all, the international system has its quirks, but it wasn't a huge change from what the kids were used to in the U.S., and I think that helped them integrate pretty quickly.

STX (general matriculation exam) = broad range of studies to start, and then students start specialized studies on humanities, social sciences, or natural science. it qualifies students to go to Danish business academies, universities, and technical or design schools.HTX (higher technical exam) = focus on technological and scientific studies but includes some general studies. After the foundation classes, you have to specialize in natural sciences, IT and communication, or technology. Again, you usually go on to a university for higher education after that.HHX (higher business exam) = focus on business, international, and socio-economic subjects but includes some general studies. You have to specialize in languages, economics and languages, or economics and marketing. Usually, you go on to a business school or university afterward.hf (higher preparatory exam) = broad range of subjects in humanities, social sciences, and science like STX, but it is a 2-year program instead of 3 years. It offers electives and qualifies students to go to Danish business academies, universities, and technical or design schools.

Oh, and we shouldn't forget about efterskolen!!

That's a school where kids can go during their teen years (usually 14-18). They can attend for maybe 1-3 years and during that time, they can learn with a specific focus on a subject area (e.g. theater, sports, music, animation, etc.), live communally, form friendship bonds with other students, and really develop themselves on a number of levels. These do cost money, unlike the Danish public schools, but there are many of them around Denmark, and many young people take advantage of these opportunities.

The efterskoler are, in some ways, similar to the Danish højskoler, which are institutions where any member of the community (e.g. families, pensioners, adults, etc.) can go and study a subject (or a variety of subjects) for a few days or a few months without the stress of tests or grades. They focus on communal living and democratic citizenship, and of course, it's a great way to continue your own personal development after graduation. Many people will take vacations by going to study at a højskole, and even one of our U.S. friends was here studying at one for the last four months!

* * *

So there you have it! I'm sure there are some disputable statements in here, but this is accurate as I can be based on my own knowledge and experiences.

I know there is some educational reform going on right now in Denmark, and I think they are actually doing away with 10th grade and combining a couple of the pathways, but for now, this is what I (think I) know.

* * *

In closing, I am glad we chose international school for the kids.

I love that they are making friends from all different backgrounds and cultures. It's so moving when Harrison starts doing Polish Duolingo so he can speak to his friend in their mother language or performing an African dance. I like that Khloe wears jewelry from Zimbabwe and has developed a love of food from Brazil. I think it's nice that Kaden is actively noticing the differences between teens from different cultures and can pick out the values that he admires as well as the behaviors he finds objectionable.

I think it's also very good for them to have teachers from other parts of the world. There will always be clashes between students and teachers who have different learning/educating styles, and I think having to be able to cooperate and manage the cultural differences as well will make the kids exceptionally good at collaboration and working across teams with different backgrounds in their future careers, whatever those might be.

Finally, I really like the emphasis that is put on personal choice, respect, social learning, and individual responsibility. I love that the kids are trusted to go on overnight school trips as early as 2nd grade, to live communally during that time, to manage their own behavior and food preparation, and to explore and experience new places.

It's all so different than my own educational experience. I find it interesting (if not a tad overwhelming), and I hope it was somewhat interesting for you to hear about, too!

Missing you all ❤️

ReplyDeleteWe miss you all, too! It's such a good neighborhood.

Delete